By Ben King Business reporter, BBC News

- Published

British employers planned making redundancies at close to a record level in September, as the second wave of coronavirus took its toll on jobs.

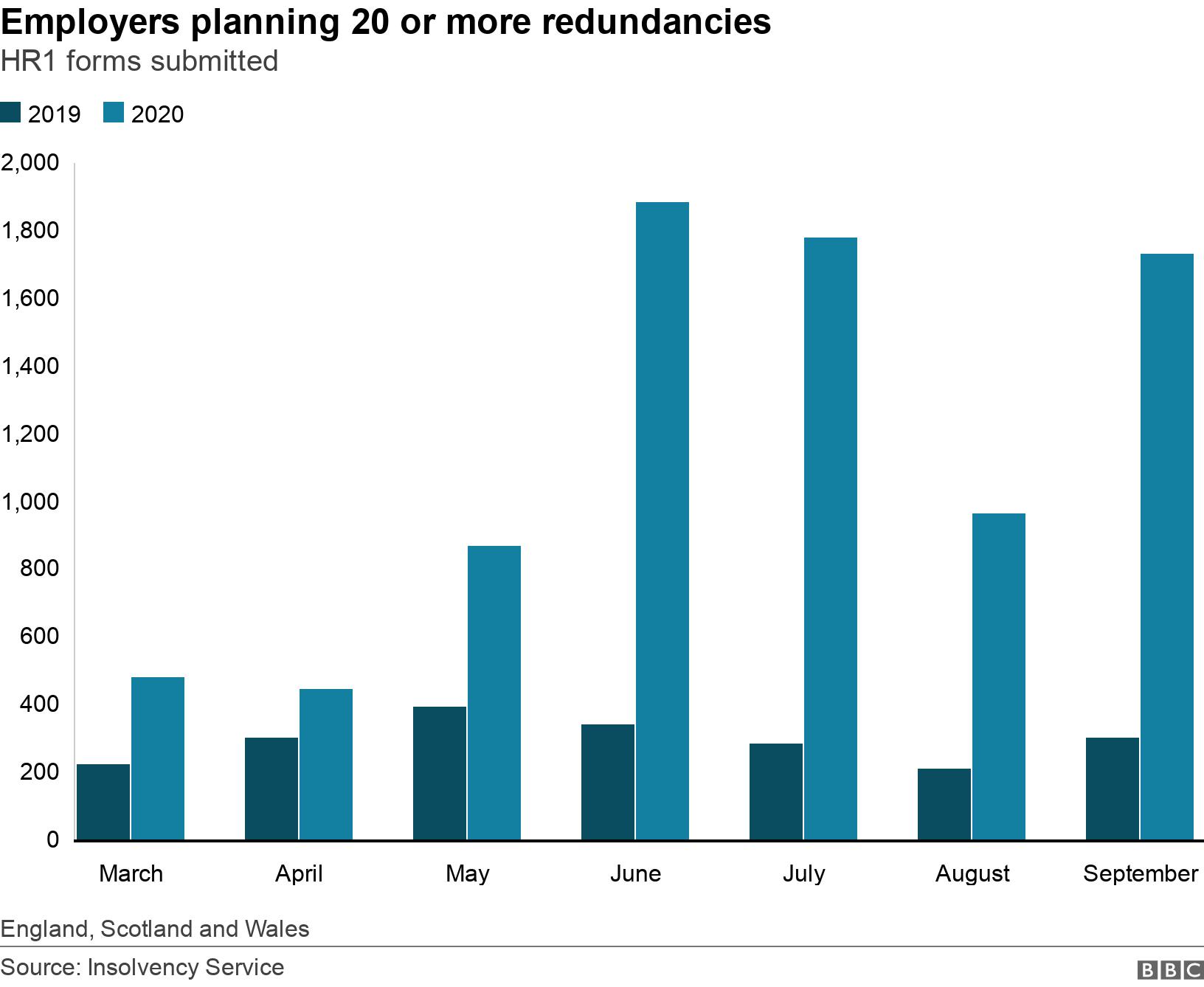

Some 1,734 employers notified the government of plans to cut 20 or more posts, close to the peak levels seen in June and July.

Those were the highest levels seen since 2006, the earliest date for which figures have been published.

The data was released to the BBC after a Freedom of Information request.

September saw an increased number of restrictions introduced around the UK as a second wave of Covid-19 infections took hold.

A number of big businesses, including Lloyds Bank, Shell, Virgin Atlantic and the Premier Inn owner Whitbread were among those announcing plans to cut staff.

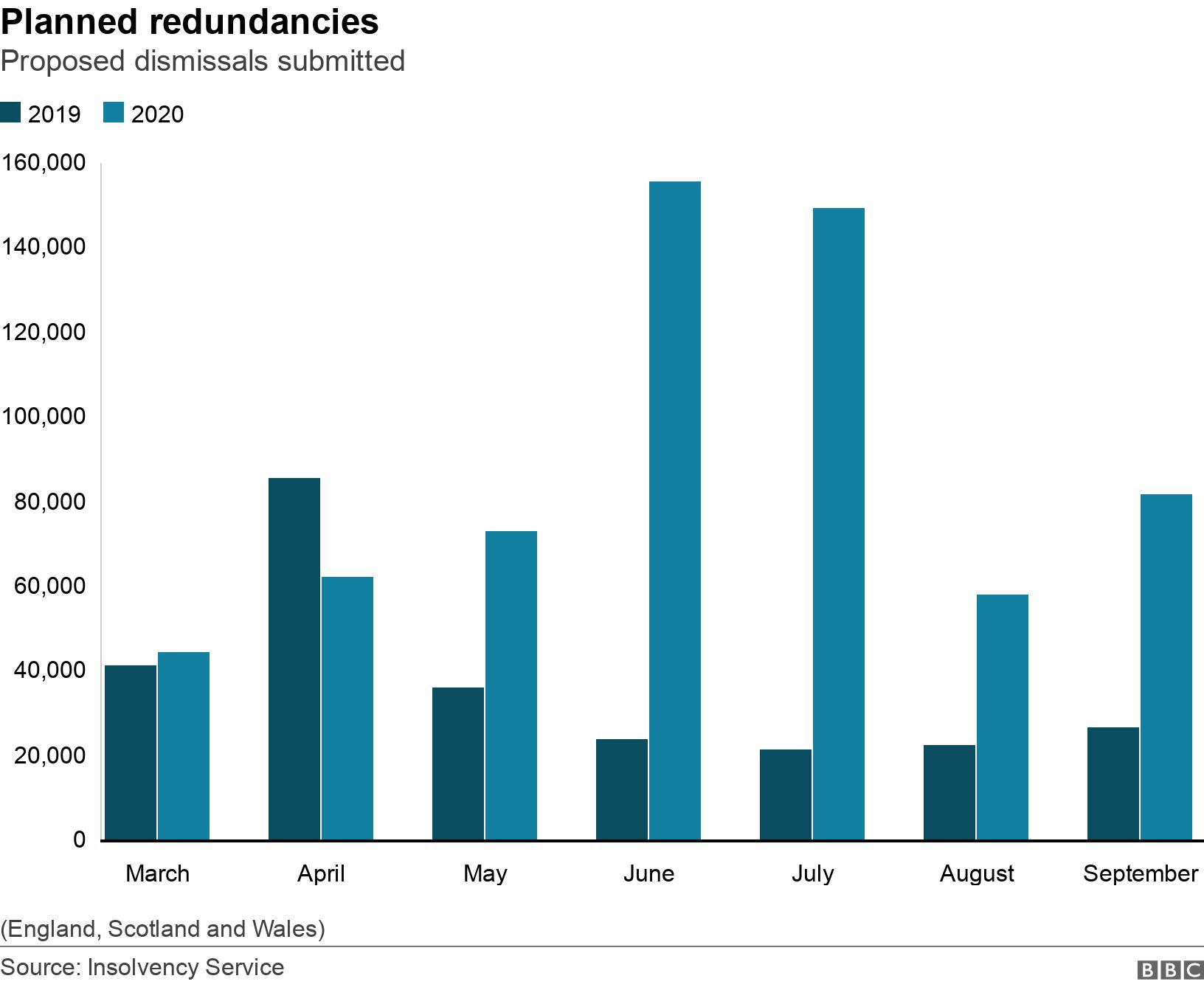

The total number of positions notified as at risk in September was 82,000 - down on the peak in the summer, but three times the level of the previous September.

"What we may be seeing is firms who were intending to bring people back deciding that they can no longer do it because of the worsening economic climate," said Tony Wilson, director of the Institute for Employment Studies.

How will the end of the furlough scheme affect redundancies?

In September, employers were asked to pay a greater proportion of the costs of staff members on furlough, with the scheme due to end completely on 31 October.

On 24 September, Chancellor Rishi Sunak unveiled a new scheme to support jobs hit by the crisis, and in early October he announced further measures to support employment at businesses in areas hit with new local restrictions.

A government spokesperson said: "Protecting jobs is an absolute priority and our Plan for Jobs will help more businesses safeguard them as we head into winter. Our updated Job Support Scheme makes it easier to keep staff on and further adds to our £200bn Covid-19 response to protect jobs, incomes and businesses."

October's redundancy figures will be the first to cover a full month when employers have known what will replace the furlough scheme.

"If the new job support scheme goes down well, we might see some of these redundancies not being completed. But if employers don't take it up, we might see another uptick in October," said Mr Wilson.

'The job market is pretty dire'

Early this year, business was picking up at Sarah Burridge's company in Leicester. She worked in administration at a specialist asbestos removal company.

2019 had been tough, but orders were coming in again. Then the pandemic struck, business dried up, and Sarah was put on furlough.

While the rest of the country saw restrictions lifted in the summer, Leicester went into a second lockdown. Sarah's bosses told her they couldn't afford to keep her on, and she was made redundant at the end of August.

She has some modest savings from an inheritance.

"That's meant to be my pension," she says. "My youngest son was disabled, I had to stay at home longer and look after him, and therefore I have a very small pension pot."

It means she can't claim universal credit while she's out of work - and she fears she may have to draw on her savings to make ends meet.

Sarah is looking for new jobs, even considering parcel delivery and courier work, though it's not ideal to start such a physically demanding job in her mid-fifties.

"The jobs market is pretty dire at the moment," she says. "There's very little out there, and what is out there, there are so many applicants for it."

Employers are obliged to notify government when they plan to make 20 or more staff redundant in any single "establishment" using an HR1 Advance Notice of Redundancy form.

This data picks up an increase in redundancy plans long before the Office for National Statistics' redundancy figures, which appear with a lag of several months.

ONS numbers showed 227,000 redundancies between June and August, a record increase of 113,000 on the previous three-month period, confirming the surge in HR1 redundancies reported by the BBC in the summer .

Firms often make fewer job cuts than they initially plan. However, any redundancy process involving fewer than 20 people doesn't need to be reported, so in the past the ONS redundancy figures have mostly been higher than the HR1 numbers .

Employers in Northern Ireland file HR1 forms with the Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency, and they are not included in these figures.

from Via PakapNews